“Curries consist in the meat, fish or vegetables being first dressed [cooked] until tender, to which are added ground spices, chillies, and salt, both to the meat and gravy in certain proportions; which are served up dry, or in the gravy; in fact a curry may be made of almost any thing, its principal quality depending on the spices being duly proportioned as to flavour, and the degree of warmth to be given by the chillies and ginger. The meat may be fried in butter, ghee, oil, or fat, to which is added gravy, tyre [yogurt], milk, the juice of the cocoanut, or vegetables, &c. All of these, when prepared in an artistical manner, and mixed in due proportions, form a savoury and nourishing repast…. ” – Dr. Robert Riddell, Indian Domestic Economy and Receipt Book, 1841

“Do you eat Indian Food?” Is one of the most asked questions I get from Indian people meeting me for the first time and finding out that I’ve moved recently to India. It’s difficult to know how to respond to that. Sometimes, because I’m terrible I respond with a calm deadpan no, just to see what happens. Sometimes I try to earnestly explain that my first taste of cardamom did not, in fact, occur on the sub-continent of India. But I honestly think that my most used response of a joking I’d better is actually the most accurate one, because, frankly, if you live in India, how could you possibly avoid Indian food? Indian food isn’t a rare species, it’s not hard to find. What can be hard to find is…anything else.

But before diving into the wide wonderful world of “continental” cuisine in India, let’s address the question “what do you MEAN by Indian food?” Because much like the idea of a national Indian language is, frankly, laughable once you meet more than one actual Indian person or travel anywhere in any direction for any length of time and see how many languages and dialects people speak here. In the selfsame way a unifying concept of Indian food is one of those things that you can thank English colonizers for in the form of the ubiquitous much defiled, much glorified curry.

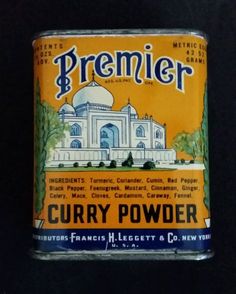

So, what is curry, and where does it come from? Surprisingly enough, it’s an older concept than you might think, and it didn’t come from India, it was, in fact, inflicted on it. The first mention of the term curry in a Western cookbook comes from an English cooking manual from 1390 called The Forme of Cury, a book compiled by some 200 chefs under the directive of Richard the II because I guess being the Richard that DIDN’T slaughter most of his relatives left hm with a fair amount of time on his hands.

There is some debate about the term cury, although many agree that it has something to do with cooking or being hot, given its derivation from the French cuire, to cook. However, there are some that claim curry comes from the Tamil word kari, which was a thin spiced sauce served in Southern India to Portuguese explorers and spice merchants.

Which ever way you slice (or stir) it, and whoever happens to be correct, the fact is that the spice trade had been bringing a steady stream of ginger, pepper, cloves, cinnamon, cardamom and coriander from India to Europe for centuries by the time the British East India company first set foot on Indian soil. When encountering a dish prepared by the kitchen of the Emperor Jahangir, British traders couldn’t get over its similarity to the chicken pie from a popular recipe book of the time, The English Hus-wife’ by Gevase Markham.

Regardless of what actual Indians in India were eating, the various European influences living in India and returning home to their native countries carried with them an idea of Indian food, which often bore no relation to the food of Indians themselves. Take a look at this poem by William Thackeray entitled Poem To Curry:

Three pounds of veal my darling girl prepares,

And chops it nicely into little squares; Five onions next prures the little minx

The biggest are the best, her Samiwel thinks,

And Epping butter nearly half a pound,

And stews them in a pan until they’re brown’d.

What’s next my dexterous little girl will do?

She pops the meat into the savoury stew,

With curry-powder table-spoonfuls three,

And milk a pint (the richest that may be),

And, when the dish has stewed for half an hour,

A lemon’s ready juice she’ll o’er it pour.

Then, bless her! Then she gives the luscious pot

A very gentle boil – and serves quite hot.

PS – Beef, mutton, rabbit, if you wish,

Lobsters, or prawns, or any kind fish,

Are fit to make a CURRY. ‘Tis, when done,

A dish for Emperors to feed upon.

The idea that curry is a powder that you add on to a dish is laughable to many Indians, or, if you are Mr. India and you take your curries seriously, rage-inducing, up there with other Anglo-Indian inventions like chicken tikka masala and mango lassi, all of which are tantamount to vile curse words in our household. But that being said, while it might not be accurate to current Indian cuisines, which themselves have been fundamentally altered by an influx of New World foods like the potato, the tomato, and most importantly, the chili (yes, that’s right, chilies came to the Old World on the ships of Portuguese traders and have only been a part of Indian cuisine since the 1600s. You can learn a lot about this in Lizzie Collingham’s excellent and informative Curry, A Tale of Cooks and Conquerors, the reality is that this is all co-evolution, because as long as spices have been pouring into Europe from India they have been associated with an idea of “Indian food” that might exist only in the imaginations of English housewives.

The question then remains, does that make it less real? If an international concept of Indian food existed as a conversation between East and West, a global dialogue in which recipes are lost, and found, in translation, then it makes perfect sense that iterations of Indian food outside of India would be half the invention of British traders who had developed a taste for the Indian cooking provided by their servants and native mistresses, and half the creation of Indians abroad trying to replicate the tastes of home with foreign ingredients. Filter that through the prism of commercial use, that is, constructing a restaurant whose menu is exotic enough to be exciting and familiar enough to be comforting, and there you have the naan-tandori-dal-paneer-rice mix that calls itself Indian food outside of India. And it’s not entirely false, even if it is different.

The primary cuisine that is known in the US, or at least, in my experience of eating Indian food before Mr. India entered my life like an avenging angel of Biryani, is a sort of Northern Indian fusion, heavy on the ghee and the cream, but also more rice-based than many North Indian cuisines typically are, because hey, if it’s Asian that means rice, right?

But that in and of itself is changing, as immigrant populations pour in and palates adapt themselves to more and more spice, not just heat, but spice, the variety of strong distinct flavors pulsating through some Indian dishes. Slowly but surely the dosa, a South Indian delight, has made inroads, sneaking its way in as a kind of crepe-burrito fusion item, winning hearts and minds. The first time I had any alternative from these two options was dining at South Indian restaurant at 28th and Lexington (where all Indian restaurants come to die in New York) and sampling a drink that was disturbingly salty (because for me, the amount of salt that any drink outside of a margarita should contain is…zero).

The food, which I later understood to be the cuisine of Kerala, was, like so many Indian dishes I have tried since that day, similar but different. Because it’s both it really is. I can’t say that much that I’ve had in India, barring a few fruits and vegetables, is wildly different from anything I’ve ever had before. A lot of it is just better. The curries I’ve had, and made, real curries with whole spice bases and pureed onions and garlic and tomatoes and ginger that whip themselves into a luscious blend, they aren’t wildly outrageously different from what I’d had before. They have the same spices, those dried roasted gems of flavor that have traveled the world from Ancient Rome to modern Sweden just to make food taste like something.

The bane of Mr. India’s existence.

Of course, the reverse is also true. Most other global cuisines that I’ve sampled in India are modified for an Indian palette, and as such make you feel like you are constantly eating Indian food, even when the sign on the door says Thai. If mango lassi is a sin, which according to the gospel of Mr. India, it is, than chili paneer would surely be grounds for execution in Han China, and butter chicken pizza would have earned you an excommunication in 17th century Naples. And that’s okay, really. Why shouldn’t food be adapted and remade, refashioned and used for the local need? Look, it would be nice to have more “authentic” options, although that gets into a whole conversation about authenticity as a construct which I simply don’t have time for today, do you? But the truth is, the answer to if I eat Indian food is really, of course I do. What option do I have, really? One way or another, we all go down the Silk Road, and the provisions we take are curried.